What is “Christian” Art?

13 Apr 2012 8 Comments

in Aesthetics, Guest Posts, Philosophy, Theology

Editors preface: For quite some time, I have wanted to showcase the work of erudite friends of mine for a wider audience than those who are typically exposed to their scholarship. Anticipating that I would have little time to devote to writing during the months of March and April due to a trip I had planned to Israel, I asked my friend, James Beal, whether he would be interested in sharing any of his work here. James graciously obliged, and I am happy to say that there is no one else’s thought for which I would rather use this website as a platform for broader discovery.

James is an attorney in Chicago with an expansive interest in a variety of subjects, including philosophical theology. He adapted the following essay from a dialog he conducted on the topic of aesthetics which I further edited for a more general audience. While James’s subject matter might seem a bit abstract on first blush, let’s be honest: A lot of ostensibly Christian art is really, really terrible. In fact, it is so egregiously poor that multiple different theologians have taken to analyzing why this could possibly be the case, from Scott Nehring’s medium-specific prognosis in “Why Are Christian Movies So Bad?” to Tony Woodlief’s more general yet scholarly “Bad Christian Art.” Nathan Kennedy’s blog went so far as to devote a two part series exploring the “suckage of Christian art,” and even the Gospel Coalition has taken to mounting discussions between various church leaders on the topic.

James’s essay intentionally leaves some questions unanswered, e.g. How are Christians supposed to promote good art, let alone nurture budding artists? Is there an assertive, one might even say missiological purpose behind Christian art as such? Are some contexts more and less appropriate venues for the production, distribution, or consumption of Christian art? Nevertheless, I believe his perspective advances the discussion instructively, and it is my privilege to recommend it for your reflection and edification.

I have listened to Bach’s cello suites. And I have listened to some of his overtly religious works, such as St. Matthew’s Passion. They are both beautiful. Are they both “Christian?”

It is difficult to describe religious experience compared to, say, religious exercise. An experience is inherently subjective while an exercise is objective. An exercise can be observed. It can be prescribed and followed. What happens in the mind or heart of the adherent during the course of the exercise is different from the exercise itself, and that happening is experience.

Art may not only be produced, it may be experienced. In fact, most art is meant to be experienced; it is meant to evoke thoughts and feelings of one sort or another. Can art be distinctly Christian in this evocative capacity? I believe it can.

Christian art is defined by a representation of at least two key elements: sacrifice and fealty. Thus, experiencing fealty and sacrifice in the context of something like an artistic element of Christian worship is different than experiencing the beauty of nature. Bach’s cello suites are like experiencing nature.

Don’t misunderstand me; I am not degrading natural beauty. I have been to the beach at night in coastal South Carolina and Florida. The combination of sensations—smelling the ocean breeze, seeing the stars glimmer, hearing the waves crash—is a powerful experience. One wonders if this is the sort of beauty that Adam and Eve encountered each moment before they were banished from the Garden of Eden.

But whatever our most distant ancestors experienced in antediluvian paradise, on the plains of Africa, or wherever, many of us know the Christian story, and we know it well. And that story is set apart from our daily life as animals on a physical planet. Human introspection, human ideas about how to organize and effect both our own lives and society, human thoughts about the physical nature of the universe and all that is in it—these concepts help define us as specifically human creatures. So, too, do vice and sensual experience, which are not always the same.

But, think about all of these things and then compare them to Christ’s words in Luke 9.23:

Then he said to them all, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me.”

Where does that come from? That is totally different from a person’s typical experience with nature, with ideas, with another human, or with another human’s creation, such as art. What Christ articulated in this short passage is a glimpse of another layer of existence, an existence not dedicated solely to our physical and societal needs.

This is not to say that humans do not create things that remind us of, even engulf us in the fundamental basis of the good news of God’s salvation through Jesus Christ: sacrifice and fealty. We do create things that specifically attempt to evoke this response, that attempt to raise our awareness of fealty and sacrifice. And those are the sorts of created things that are “Christian.” Everything else is something different. That is not to say that everything else is bad—hardly. But it is different from a distinctly Christian creation.

There is another key element of the representation of the Christian ethos in art, and that is love, or charity when understood in the old way as an altruistic, concrete, sincere expression of compassion. Sacrifice, fealty, love–these three things define Christ’s existence. He sacrificed his life in fealty to God the Father and for the love of us. This is the Christian story. And art, which is accurately called “Christian” is defined by these three elements.

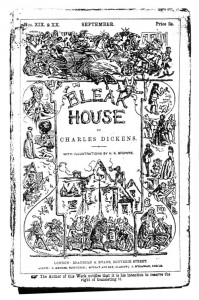

From this perspective, I would call Bleak House by Charles Dickens a Christian novel. Dickens’ representation of uncompromising love in the character of John Jarndyce vis-à-vis the love he shows his wards and even to rotten Mr. Skimpole is a fundamentally Christian portrayal of a character. In fact, Dickens is perhaps most “Christian” in his representation of prideful, dishonest, cruel, and folly-ridden villains. Dickens’ concept of evil embodied by these characters is fundamentally Christian because it purposefully represents the opposite of sacrifice, fealty and love. By doing so, Dickens’ villains reinforce the importance of those elements through impactful, negative counterexample.

In contrast, purely or simply beautiful art like Bach’s cello suites may be understood as “primitive” in the philosophical sense of the term. When Rousseau idolized infancy and simple-ness in works like Emile, or On Education, he expressly longed for the primitive. But if one accepts that humanity has left the Garden and tried to erect for ourselves some firm and steadfast structure reaching beyond the primitive with profoundly deleterious results—a process the Bible discusses in the story of the Tower of Babel—then the strictly simple, primitive nature of humanity is presently lost to us.

This fundamental fact of the loss of wholesale, social innocence or primitiveness is why we talk about “duty” and “sacrifice” and “striving for the greater good” even in secular contexts. What separates the secular version of these things from the Christian version is that they are tied to a man’s or a group’s imagined sense of right, virtue, or glory instead of being tied to those first relationships we found ourselves a part of from the beginning of time, like family or community. When we promote some sort of altruism or durable significance beyond whatever we would normally do by a sort of God-given default, we are acknowledging that we have moved beyond the primitive.

Eden and Babel are not the same. They are opposites. Eden is permanent even if its full recovery is lost to us right now; Babel is “happening” right now but frustratingly never finished. Put more philosophically, Babel is the idea of one person’s or one group’s action against another person or even against nature itself as a whole. Eden is the idea of “permanence” as true home, as perpetuity and peace and situated place.

So what does this have to do with art? Purely aesthetic experience—say, of a cello suite by Bach or a beautiful lyric poem—is not Babel. But neither is it the whole of Eden. It is more like a constituent element of Eden. Because of the distorting effect of sin, we do not experience the whole of Eden absent sacrifice, fealty and love. These are the keys that unlock for us a glimpse of the serenity from which we came and towards which God desires to ultimately locate us in eternity.

Returning to the illustration of English literature, these three elements converge powerfully and beautifully in Dickens’ Bleak House when Nemo, the law writer, interacts with the poor sweeper boy, Joe. Even though both characters have their problems, Nemo eventually dying of an opium overdose and Joe dying consumption, there are brief moments of distinctly Christian representation, e.g. when Nemo gives Joe a portion of his meager earnings with no strings attached or when Joe sincerely thanks Nemo for his kindness without any pretense or expectation but also without false humility.

A similar thing obtains in Charlotte Brontë’s magnum opus, Jane Eyre, through the juxtaposition of its eponymous protagonist with the character of her cousin, St. John Rivers. Both are ostensibly “Christian” figures, but it is Jane who achieves something closer to the unlocking of Eden while John remains counter-intuitively trapped in Babel. St. John expresses a single-minded obsession with working as a missionary; he implores Jane to marry him so as to be his helper, so as to partake in this all-important mission. But Jane refuses, desiring instead to experience her life in the company of those she loves and who love her. Late in the novel, she realizes a large inheritance and decides to divide it evenly between herself, St. John, and St. John’s two sisters—much to St. John’s chagrin. He would prefer that the whole of the inheritance be devoted to his missionary work. Jane persists in her course of action and eventually departs the company of her family for that of Mr. Rochester, a former suitor who has been struck blind since his last encounter with Jane. Despite his state of relative debilitation given the early 19th century setting of the narrative, Rochester is still deeply in love with Jane, who concludes that her true aspiration is to be nothing more than his wife in the countryside at Thornfield Manor.

Bronte’s representation of Jane is the that of a character whose central desire is for the “permanent” rather than something that is “happening” yet never finished, and her irrevocable divestment of financial resource to the benefit of her extended family coupled with her devotion to Mr. Rochester despite his functional decline in station fortifies this. Similarly, Nemo’s gift to Joe was a pure gift, given only for love and met by Joe’s sincere but not unduly humble thanks in Dicken’s Bleak House. These represent the story of Christ more compellingly than a thousand missions of Bronte’s St. John to the farthest flung corners of the world, let alone the construction of an indestructibly prosperous, healthy, secured state that Jane could have pursued had she kept the whole of her fortune and “married up” as far as possible instead of choosing Mr. Rochester.

These are “Christian” moments in Bleak House and Jane Eyre because they fundamentally represent sacrifice, fealty and love with a trajectory towards the permanent, with an eschewal of building some grandiose, unfinishable, always happening Babel. They represent the example of Christ, emphasizing Eden’s quiet to Babel’s clamor. As Jesus said to his disciples:

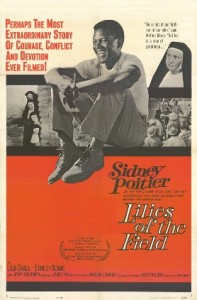

Original poster for Lilies of the Field (1963), a film adaption of William Edmund Barrett's novel by the same name for which the lead, Sidney Portier, won the Academy Award for Best Actor

And can any of you by worrying add a single hour to your span of life? And why do you worry about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not clothed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith? Therefore do not worry, saying, “What will we eat?” or “What will we drink?” or “What will we wear?” For it is the Gentiles who strive for all these things; and indeed your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. But strive first for the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. (Matthew 6:25-33 NRSV)

Christian art is that which distinctly represents sacrifice, fealty, and love unlocking the permanence of our true home. Put another way, Christian art provides a representation in music, a literary character, and so forth of Christ.